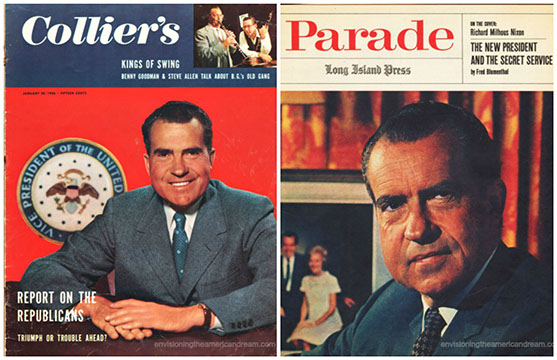

Nixon: The Face of America

By Yee Nip

Daniel Frick

Daniel Frick is currently the Director of the Writing Center, Senior Adjunct Assistant Professor of English, and an Adjunct Associate Professor of American Studies at Franklin and Marshall College. He has a B.A. from Elmhurst College as well as a M.A. in English and a Ph.D. in English and American Studies from Indiana University.

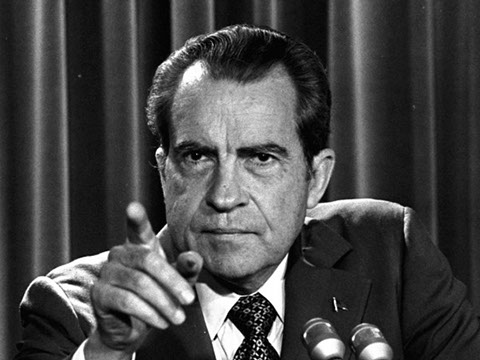

“But why are we, as a nation, so particularly preoccupied with Richard Nixon? And why are we obsessed with continually reinventing him?”1 Daniel Frick attempts to answer this question in his book Reinventing Nixon: A Cultural History of an American Obsession. During his presidency, Nixon had failed in his promise to bring the nation together. Even in his death, debate over Nixon continues with little consensus. Frick sheds light on Nixon in a cultural setting, focusing on American myths and pop culture. Using multiple cultural examples to highlight various reinventions of Nixon, Frick extrapolates these interpretations of Nixon to describe the struggle in defining a national identity.

The first reinvention of Nixon is an image of a self-made man, as a man of “pioneer spirit, work ethic, self-reliance, motherhood, tenacity, and ceaseless striving.”2 The American myth of a self-made man is the idea that a person’s position on the social and economic ladder is not a result of family legacy, but is a result of ambition and achievement. Frick utilizes Nixon’s first autobiography, Six Crises, to depict Nixon as a self-made man. Six Crises “establishes diligence as the hallmark of Nixon’s life,” a key characteristic of the self-made man.3 In fact, during Nixon’s campaign years, the most emphasized characteristic of Nixon was his work ethic. Criticism of Nixon’s autobiography questions Nixon’s honesty, contending that Six Crises distorts the truth through omission of certain facts. While Six Crises depicts Nixon as a self-made man, it also cast a shadow of doubt on Nixon’s honesty that eventually ruined his reputation. Besides the myth of the self-made man, Nixon also uses the image of the myth of national mission, “the expectation that God intends the United States to play a messianic role in world history.”4 Nixon “begs to be understood as the bearer of freedom’s flame, as an interpreter of his country’s values to the inhabitants of the world’s captive nations.”5 The myth of national mission paints Nixon as the ultimate American hero, fighting for American ideals of democracy and freedom. Portraying Nixon in a positive light, Six Crises uses the idea of a self-made man to appeal to the public’s sense of patriotism, which convinces the public that Nixon deserved the presidency.

A common reinvention of Nixon during the 1970s is a demonic image of Nixon. Frick uses The Public Burning to reveal the faults of the government and the faults of Nixon himself. The book serves “as the most powerful example of the national mission myth’s destructive power.”6 The public blamed Nixon for the problems of the United States government; suspicion turned into cynicism which turned into despair. However, for many Americans, Nixon’s faults represented what had gone wrong with the country. Thus, Frick views criticism of Nixon as a mask for the criticism of the nation and its culture and political ideology; a “demonized Nixon makes sense not because he is so uniquely wicked but because his evil nature best sums up a sick national culture.”7 Some recognized that Nixon was not to blame for the nation’s problems because he represented the failures of the American government as a whole to uphold its democratic ideals; the American public had merely used Nixon as a scapegoat for the underlying problems of the nation. This reinvention of Nixon is evidenced by An Evening with Richard Nixon by Gore Vidal, which describes Nixon “as an opportunist, amoral, and self-aggrandizing schemer” but also as “embod[ying] a only a ‘more’ naked example of America’s corruption.”8

As Nixon’s reputation deteriorated, Nixon sought to reclaim an image of integrity in his second autobiography, RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon, which “transformed the story of his public shame into one about America’s betrayal of its ideals.”9 Thus the beginnings of a cultural war had emerged. Nixon trivialized the importance of Watergate by stating that all politicians engaged in such activities and that his successes in foreign policy made up for his wrongdoings. Nixon also blamed the public for the severe consequences at Watergate, citing “the public’s appalling lack of vigilance in seeking the truth.”10 To Nixon, the increasing complacency of the American public represented a deteriorating United States. Nixon’s ability to recover from Watergate and reenter the political arena perpetuated the idea that anyone could be the president. Using The Best Man, Tyrannus Nix?, and Secret Honor, Frick shows that “Richard Nixon often gets reinvented to explore key ideological pressure points in the American myth of self-reliant individualism.”11 Nixon’s ability to claim the presidency and recover from Watergate can be attributed to the sacrifice of integrity in pursuing success. Nixon’s sacrifice of values parallels the slow decline of American values. The myth of success had been defeated with the struggles of diligent lower-class and upper-class Americans when compared to the successes of those who sacrificed their values and fought ruthlessly. By transferring blame from his own faults to the fundamental problems of the American people, Nixon sought to redeem himself.

Into the 1980s, a new image of Nixon emerged, one of “unceasing determination and the refusal to give up”; even Nixon’s opponents partook in the reinvention of Nixon as a “mythic hero.”12 Nixon’s third autobiography, In the Arena: A Memoir of Victory, Defeat, and Renewal, celebrates Nixon’s perseverance through the many setbacks he experienced. As such, to some, Nixon redeems the American myth of success, the idea that even the humblest man can achieve great things in America. It was Nixon’s resolve that allowed him to recover from his downfall at Watergate and to reassert his value in national politics and culture. To others, Nixon’s life revealed to the nation “the limits of opportunity” and the existence of an “other America.”13 After his death, Nixon was envisioned with “not just understanding but even some measure of acceptance and forgiveness.”14 Nixon is not only viewed as the culprit, but also as a victim of the emerging cultural wars and the tendency of the nation “to keep repeating the old mistakes, but with increasingly serious consequences.”15 Even after Nixon’s death, the role and image of Nixon is still being debated today, such as during Bill Clinton’s impeachment and the war in Iraq during the administration of George W. Bush.

“Because when we fight about Nixon, we are fighting about the meaning of America. And that is a struggle that never ends.”16 When discussing George Washington and the cherry tree, or Abraham Lincoln, known as Honest Abe, there is much consensus that these presidents represent an archetypal American hero, a testament to American values. When examining Richard Nixon, however, it is unlikely that one will find a more polarizing president in American history. Frick asserts that the reason behind America’s obsession with Nixon is that, in the nation’s international affairs, Americans failed to understand the country’s self-serving interests that were hidden behind its seemingly selfless actions such as during the Korean War and the Vietnam War; “critics found the image of Richard Nixon to be a convenient emblem of this self-deceiving hypocrisy.”17 Critics who viewed Nixon as the devil saw his faults and flaws as those of the nation’s; optimists who viewed Nixon as the embodiment of the American dream and the myth of success viewed his successes and triumphs as those of the nation’s. Frick reveals that Nixon has become the face of America, an American obsession, because he challenges the values that the nation was founded on—the myth of the self-made man, the myth of national mission, the myth of success. Nixon reveals to a naïve American public the self-serving interests of the government, that the myth of success is just that, a myth; “if there is any equality of opportunity in this America, it is the opportunity to be mediocre.”18

When Reinventing Nixon was written in 2008, Daniel Frick had been the Director of the Writing Center as well as the Senior Adjunct Assistant Professor of English. Having earned his bachelor’s and master’s degree in English, Frick would not only be interested in political documents, but also in other literary works, such as fictional works, poetry, plays, films, editorial cartoons and even operas. In light of the presidencies that succeeded that of Nixon’s, most recently the presidency of George W. Bush, Frick reexamines Nixon’s impact on modern day politics and culture. For example, “most contemporary editorial cartoonists have drawn Richard Nixon’s ghost as a counselor for George W. Bush on how to run a cover-up.”19 Historians are still in controversy about the origins of the political and social turmoil during this time period. Failure to reexamine the cultural wars through any perspective other than that of the “mission-myth story line” has “sentenc[ed] us to fighting and refighting the same cultural battles over and over again.”20 The culture wars were a clash of conservative and liberal ideas, of optimistic and pessimistic attitudes about the future of America. Frick focuses on pop culture and tries to offer a new perspective—that the modern cultural wars originated from the age of Nixon—examines different reinventions of Nixon to understand the United States today, and attempts to understand how those reinventions remain relevant to modern society.

Phillip G. Payne, an associate professor of history at St. Bonaventure University praises Reinventing Nixon, stating that “Daniel Frick has written a provocative and interesting study of Nixon’s persona that provides a valuable contribution to our understanding of the intersection of politics and culture.”21 Frick describes the cultural and political atmosphere of the age of Nixon (the second half of twentieth century) and how Americans’ obsession over and reinventions of Nixon parallel the conflict in establishing an American identity. Just as there are multiple perceptions of Nixon’s character and actions, there are differing versions of America’s ideology and clashing opinions as to what it means to be an American. Nixon’s success stems from his use of national myths—the myth of the self-made man and the myth of national mission. Nixon’s political opponents do not challenge these myths but use Nixon to challenge conventional American ideals. Nixon used this criticism to blame his defeat not on his own faults but on the faults of the nation in order to depict himself as a victim and arouse sympathy from his audience. Thus, “Nixon’s image became a centerpiece in the culture wars” when opponents of Nixon used him to criticize American identity.22 Frick skillfully incorporates political and cultural works in exploring Nixon’s legacy on American culture, a question that is still debated to this very day.

Offering a somewhat different perspective on Frick’s book, Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Marquette University Julia Azari echoes some of Payne’s praise but also offers criticism of Reinventing Nixon. While the book successfully captures the clash of various American ideologies that form the foundation of political debates today, a major weakness is that “the causal and explanatory relationships among art, ideas, politics, and images are unclear.23 Like Payne, Azari recognizes Frick’s thorough research in the evidence cited in the text; unlike Payne, however, Azari contends that Frick failed to connect the different realms of American culture that form the basis of Americans’ self-image. Another weakness of Reinventing Nixon is that “it passes up the opportunity to engage with the broader significance of presidential imagery for American identity and values.”24 Although Frick depicts Nixon as the prime example of controversial presidencies, including a comparison to other contested presidencies, such as those of Thomas Jefferson, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Bill Clinton, would strengthen Frick’s argument of the overreaching influence of Nixon on American values.25

Reinventing Nixon’s greatest value lies in its analysis of cultural works to reveal different perspectives on Richard Nixon. The first thing that comes to mind when one hears the name Nixon is Watergate, deceit, and shame. However, Frick skillfully uses pop culture and political memorabilia to reveal a side of Nixon contrary to the widespread demonic view of the man: an image of Nixon as a representative American, embracing traditional American ideals of hard-work and diligence. Frick shows that even when “cynicism soured people’s faith in public life” and in Nixon, optimists “opted instead for tales of private redemption.”26 At times, the vagueness of Frick’s analysis shows how Nixon’s role in American politics and culture is a dilemma that has not—and will not soon—be solved. Frick expands on Nixon to comment on American society, though he sometimes offers evidence and facts that, while interesting, are irrelevant to his thesis. Frick exposes his audience to a plethora of more obscure pop culture that goes beyond the common image of Nixon, although occasionally, Frick gets bogged down by excessive plot summary. Frick offers a fairly unbiased analysis on each reinvention of Nixon; he does not try to assert a perspective on his audience, but rather emphasizes the fact that there are multiple images of Nixon, that no one image is correct or incorrect, and that that is the reason behind Americans’ obsession with Nixon.

Frick views the 1970s until the end of the twentieth century as the Age of Nixon because the era was defined by a controversy over the image of Nixon that represented the question of American identity. The Age of Nixon was partly a continuation to the 1960s, but also a reaction to it. The 1960s were a time of political and social upheaval for American society. As the Cold War raged on, a counterculture emerged. Conservative beliefs were challenged; people listened to rock ‘n’ roll, advocated for women’s rights (including the right to abortion), fought for civil rights and desegregation, and protested the Vietnam War in an antiwar movement. In many ways, Nixon represented a continuation of the liberality of the 1960s. Nixon viewed through the myth of national mission represents a liberal image as he sought to extend American democratic ideals. For example, “Nixon’s own self-promotion as a civil rights leader…promote[d] Nixon as the last, and most successful, liberal president,” despite having been a Republican, and represented a continuation of 1960s counterculture.27

However, Nixon also represented a challenge to the radical ideas of the 1960s and a return to conservative ideals as “the American mainstream’s orthodox system of beliefs…resurged in the years following his resignation.”28 Nixon, as a representative American, embraced the myth of the self-made man as well as the myth of success and the American dream in ordinary Americans. Reducing the number of troops in Vietnam and ending the war through the Paris Peace Accords were actions taken by Nixon in direct response to the 1960s antiwar movement, as seen by a critic’s annotation of John Fischetti’s political cartoon; the political cartoon shows Nixon’s body disappearing until only his devious grin remains. While Fischetti intended to cartoon to mean that the nation had been fooled by Nixon’s charisma and that Nixon has moved away from his promise of reuniting the nation, Fischetti’s critic notes that this represents the diminishing troops left in Vietnam.29 Frick asserts that the battle over Nixon represents a time of crisis. After facing the social and political turbulence of the 1960s, a period of time which caused Americans to reevaluate their principles and national myths, the United States faced an identity crisis in the 1970s, a question of what defined America and America’s role on the international stage. Nixon served as an outlet for “political and cultural analysts and creative writers…to explore the unresolved debate over what America is and should be.”30

Whether depicted as a self-made man or the devil, whether viewed with appreciation and forgiveness or with cynicism and resentment, Richard Nixon becomes a representative American. Different versions of Nixon offer competing images of the United States itself; “the battle over Richard Nixon is a long-term battle for the nation’s future.”31

Footnotes:

- Frick, Daniel. Reinventing Nixon: A Cultural History of an American Obsession. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2008. 13.

- Frick, Daniel. 3.

- Frick, Daniel. 26.

- Frick, Daniel. 32.

- Frick, Daniel. 36.

- Frick, Daniel. 111.

- Frick, Daniel. 145.

- Frick, Daniel. 146.

- Frick, Daniel. 47.

- Frick, Daniel. 65.

- Frick, Daniel. 102.

- Frick, Daniel. 173.

- Frick, Daniel. 213.

- Frick, Daniel. 214.

- Frick, Daniel. 234.

- Frick, Daniel. 17.

- Frick, Daniel. 113.

- Frick, Daniel. 95.

- Frick, Daniel. 236.

- Frick, Daniel. 107.

- Payne, Phillip. Rev. of Reinventing Nixon: A Cultural History of an American Obsession, Daniel Frick. American Historical Review 115.2: 572-73. Web.

- Payne, Phillip.

- Azari, Julia. Rev. of Reinventing Nixon: A Cultural History of an American Obsession, Daniel Frick. Presidential Studies Quarterly 40.2: 378-79. Web.

- Azari, Julia.

- Azari, Julia

- Frick, Daniel. 147.

- Frick, Daniel. 154.

- Frick, Daniel. 233.

- Frick, Daniel. 14.

- Frick, Daniel. 228.

- Frick, Daniel. 238.

1 - 4

<

>