Revolution and the New Guard

By U-Ra Lee

Jeff Madrick

Jeff Madrick graduated from New York University and Harvard University. He is editor of Challenge: The Magazine of Economic Affairs. He is also the author of Seven Bad Ideas: How Mainstream Economists Have Damaged America and the World, in which he talks about profound impact of economists who worked in economic and political field.

Since the Great Depression in the 1930s, the 1970s was the worst decade of economic performance in the United States. With punishingly high inflation and unemployment rate, Americans came to believe that the federal government had gone too far and the revolutionary economic system should “set the stage for a different America.”1 Although not everyone discussed in this book was wholly destructive, Age of Greed: The Triumph of Finance and the Decline of America, 1970 to the Present, written by Jeff Madrick, introduces the transition of American economy and its profound influence through the stories of people who took part in leading America to the new age by bringing the national “economy to a tragic path for their own purposes.”2

To set the discussion, Madrick begins with a relatively unknown man named Lewis Uhler, “a Southern Californian, who hated the New Deal” and feared that individual liberty was “in constant danger of being taken away by big federal government.”3 Lewis Uhelr, learning from his politically conservative father, believed that the public social programs and economic regulations of government interfered with the rights of Americans, especially during an era when “high taxes were justified” by the World War II. Also, progressivism continued to spread under Franklin Roosevelt and Eisenhower.4 Such fear and anger towards the government laid the foundation for a new age from the 1950s to 1970s. Along with politically conservative people, there were others who claimed the necessity of freedom in market system and business. The most well known of those was the economist Milton Friedman. His philosophical view was that “the government social programs and regulations” were always “damaging interference with the efficient workings of an economy.”5 In the midst of rising inflation and slow economic growth, those limitations set boundary to personal liberty and further opportunity to improve business and market system, according to Friedman. Friedman agreed with how many other Americans including Uhler felt about government. He thought American production industry would develop much faster without strong federal government. By seeking to eliminate governmental social policies including Social Security, minimum wage and unemployment insurance, Friedman provided the intellectual guidance “for a reversal of the progressive evolution of the nation.”6

While Friedman and Uhler represented Americans’ new perspectives toward government regulation, some practitioners of greed “took the economy along an unfortunate path.”7 Joe Flom, for example, was a lawyer, specializing in mergers and acquisitions (M&A). He was famously known for his involvement in takeover battles that began in 1970s when loss of American market share and foreign competition pushed big business to acquire smaller ones. As the stock prices lowered due to inefficient generation of earnings by the conglomerates, ambitious Wall Street bankers including Flom started a takeover wave seeking for more profitable opportunities. This hostile movement made companies to “regularly acquire target companies against the whishes of their current management,” in an effort to win a takeover battle.8 The takeover movement provoked by M&A lawyers at Wall Street transformed the way American companies were managed. Companies desperate to raise the value of their stock to avoid a takeover started to focus on improving profits in the short run. Wages lowered and employees were fired as greedy Wall Street specialists like Flom enlarged the deal size and took a percentage of the transaction price of deals. From the 1970s to the 1990s, the size of deals of merging companies went from “$150-200 million to $15-20 billion.”9 The profit-motivated takeover battles made American business and economy far too risky and lean with unhealthy economic process on balance. Another prominent participant of greedy Wall Street was Ivan Boesky, known for his involvement in a Wall Street insider trading scandal. Boesky, who was very profit-driver, discovered that risking arbitrage was a dangerous yet sure path to attain the immediate wealth he desired like any other arbitrageurs that made the most profit from the takeover movement in 1980s. In 1986, Boesky was eventually investigated by the U.S Securities and Exchange Commission and received a prison sentence for amassing more than $200 million by betting on corporate takeovers. Although Boesky’s insider trading scandal was the most widely known incident of the era, it was only one of many financial “banditries done in the open, under the glare of increasingly negligent regulators.”10

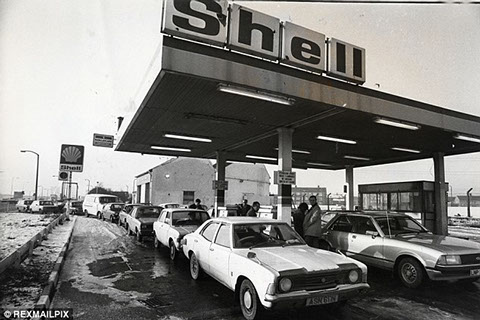

Madrick then names presidents and political figures that further reinforced the changing national attitudes. Richard Nixon, who became president in 1969, did not have his political focus on economic policy. His administration put its emphasis on domestic and international diplomacy. Caught up in the Watergate scandal and the Vietnam War, Nixon supposed international diplomacy was a priority, even though the national economy was in a steep recession with “unemployment rate at 7 percent, its highest level for the decade.”11 In 1973, unemployment, along with “crop failures and quadrupled OPEC oil price” raised inflation rate and consumer prices astronomically.12 As Madrick also mentions, Nixon was the last president who could have stopped the inflationary surge with moderate pain before it continued for another decade. Two presidency terms after Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter inherited an economy that was emerging from a recession. During Carter’s four years as president, however, both inflation and unemployment rate worsened considerably more than any time before his presidency. The annual unemployment rate went from “7 percent to above 9 percent” and “slowdown in the rate of productivity” was evident.13 Even though the Carter administration passed Proposition 13, which called for sharp reductions in the property tax cuts, it was well aware that there was a growing public opinion in favor of tax cuts. They had already “switched the direction of economic policy three times,” and many Americans had begun losing faith in government solutions. As a result, citizens started movements demanding diminishment of government ruling over economy and business.14

As the government slowly started losing its power and control over domestic business, new technology in the new age led to a remarkable change in mass production and the rise of distribution giants by the 1990s. There were three big entrepreneurs who represented this period of time when “standardized and affordable products” were mass-produced with “innovation and entrepreneurialism” : Ted Turner, Same Walton and Steve Ross.15 Sam Walton was a entrepreneur, best known for founding Wal-Mart. Symbolizing the beginning of mass production, Wal-Mart became America’s largest company, and raised inventory management through use of computer technologies, which was the most innovative way to manage business in 1970s. Because the government regulations on business was weakened from the 1970s to the 1990s, Walton, who simply saw productivity and profitability, “only paid $1,300 of income a month for worker” who worked forty-hours a week.16 Walton even locked workers in stores at night and hired illegal workers for below minimum wage. He made an effort to raise profits and productivity of production by minimizing the use of warehouses and enforcing stern labor practices, which led Wal-Mart to produce a much higher sales volume per employee than its competitor. Although many American consumers in 2000s answered positively about Wal-Mart’s low prices, productivity along with capitalism in business was losing its historical meaning in a political environment that tolerated low wages and worker insecurity. Ted Turner, on the other hand, built the new, independent-minded news channel CNN. Such new information-gathering innovation, however, was acquired in a period when “ to survive meant becoming a corporate giant.”17 In the new age of the 1990s, government’s concerns about the dominance of news by a few organizations were disregarded as free market economic thinking grew in influence and such transition caused involvement of financial criteria in the industry of entertainment, news, and communications. When there are “strong financial incentives to homogenize news and entertainment, and government stops demanding independence and variety of ownership,” the dangers in broadcast industry are evident.18 Serious news was discarded in favor of entertaining, and locally produced documentaries were no longer visible on TV as a result of bigger broadcasts taking over their spots. Attractive features replaced hard news on newspaper and TV news, which caused the range of political views on major news channels narrowed, with very few exceptions of conservative channels including MSNBC and Fox News. In the name of size, marketing power and dependable information became “scarcer and informational and cultural diversity narrowed.”19

With the clear purpose of explaining the transition of American economy in terms of rebalancing between government and business, the author Jeff Madrick puts emphasis on analyzing how and why vital purposes of government were rejected and what brought a new stage of American economic history in the 1970s. He contrasts the difference between an economy under strong federal government regulation and business without harsh limitation. He also explains how such change between two periods was about brought about by economically and politically influential figures in history. Madrick also shows how the separate stories of participants of such economic movement become integral parts of a bigger picture as he goes through presidents, economist, financiers and business pioneers of the 1970s, including Richard Nixon, Joe Flom, Ted Turner and Ivan Boesky. Although “no one in this book is wholly destructive,” each of their theories, practices, decisions and beliefs is described to demonstrate “the way people reacted to crisis and change.”14

From the 1970s to the 1990s, Jeff Madrick had several positions in the journalism field, including Wall Street editor of Money Magazine, finance editor of Business Week Magazine, and head editor of Challenge: The Magazine of Economic Affairs, which gave him a more critical and clever perspective in viewing the transition of the American economy pertaining to government regulation and intervention as he worked as journalist during the period when the major shift in economy took place. Because he was responsible for accurately reporting what was happening in economic and political world by fully understanding the relationship of two, Madrick was able to learn how to make connections between government and economy. He also majored in economics in New York University and Harvard University, where he was able to learn basic foundation and development of national economy throughout the history. His career experience as an economic policy consultant and analyst may have given Madrick deeper understanding of the relationship between government policy and economy of its nation. The time period when Madrick wrote this book had a great influence on its quality and contents as the time between late 20th century and early 21st century showed the most recognizable transition from the beginning of financial revolution to the start of the new age. Just as he mentions, “it was not as if there were no precedents for these excesses,” Madrick was able to portray how the current state of American economy came to be as it is now by comparing the past and current era of America.20

In his insightful review, Sebastian Mallaby, the Paul A. Volcker senior fellow on the Council on Foreign Relations, contends in an article of New York Times that the theme of Madrick’s Age of Greed: The Triumph of Finance and the Decline of America, 1970 to the Present “is slippery” and that “there are some confusion and errors,” although he makes “generally good use of secondary sources.”21 According to Mallaby, Madrick was unclear on his position throughout his work and did not correctly imply the theme shown in the title, Age of Greed. Another reviewer, David Greenberg, who is a professor of history, journalism, and media studies at Rutgers University, stated in an article for the Washington Post that Madrick’s work is very novel in a way that “it traces the origins of the problem not to the Bush or Clinton or even Reagan years, but all the way to the late 1960s.”22 Greenberg also added that the book was unclear on “difference between those rogues whose greed led them to run afoul of the law and those whose greed the system has in fact smiled upon.”18

Overall, Jeff Madrick’s book, along with the stories of a variety of figures, provides understandable, yet critical analysis of revolutionary economic era and introduction of the new age. With extensive information and understanding, Madrick makes it fairy easy to see connection between the integral parts taken by historically significant participants of economic movement. Although it would have been more explanatory if the author defined economic terms more specifically, supplying a plethora of facts based on the numerical data and comparison of those data between different decades made the transition look clearer. His sophisticated idea that “the new age was made by people, and how they reacted to crisis and change” was inevitably demonstrated through a condensed summary of little parts that took part to make a bigger picture later in the future.23

Throughout his work, Jeff Madrick asserts that the severe economic crisis and noticeable transition of financial state of America was not caused by single event at one moment of history. The position of author can be seen by how he covers different people in different fields and recognizes how each of those figures contributed to the past fifty years of American economic history. As it was shown through Lewis Uhler, who was “advocate of elimination of government intervention and regulation,” Madrick conveys his view that the 1970s were a continuation of the early alteration of national economy from 1960s, which was when Americans started to doubt the credibility of the federal government as a result of its failed attempts to the recover economy after the Great Depression.24 Madrick then adds on by explaining conversion of economy of America and the influence of relationship between government and business, which is still going on even now in 21st century. Connection shown starting from Walter Wriston to Jimmy Cayne lets further comprehension of how Madrick sees history of economy as a whole picture with variety of parts filled up by different causes.

In conclusion, Jeff Madrick objectively describes in his latest work Age of Greed: The Triumph of Finance and the Decline of America, 1970 to the Present how the current state of American economy is “the culmination of forty years of growing power and weakened government.”25 Although the book ends with the story of Chuck Prince, “the age of greed continued” and those ages will come together to make a bigger picture of American economic history.26

Footnotes:

- Madrick, Jeff. Age of Greed: The Triumph of Finance and the Decline of America, 1970 to the Present. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011. x

- Madrick, Jeff. Xi

- Madrick, Jeff. 3

- Madrick, Jeff. 5

- Madrick, Jeff. 27

- Madrick, Jeff. 37

- Madrick, Jeff. Xi

- Madrick, Jeff. 73

- Madrick, Jeff. 73

- Madrick, Jeff. 95

- Madrick, Jeff. 57

- Madrick, Jeff. 67

- Madrick, Jeff. 151

- Madrick, Jeff. 151

- Madrick, Jeff. 125

- Madrick, Jeff. 133

- Madrick, Jeff. 127

- Madrick, Jeff. 143

- Madrick, Jeff. 143

- Madrick, Jeff. 401

- Mallaby, Sebastian. “Why We Deregulated the Banks.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 30 July 2011. Web. 31 May 2015.

- “Book Review: ‘Age of Greed’ by Jeff Madrick.” Washington Post. The Washington Post, n.d. Web. 31 May 2015.

- “Book Review: ‘Age of Greed’ by Jeff Madrick.” Washington Post. The Washington Post, n.d. Web. 31 May 2015.

- Madrick, Jeff. 9

- Madrick, Jeff. 397

- Madrick, Jeff. 397

4 - 4

<

>