¡Si Se Puede! Yes We Can!

By Taylor Gonzales

Randy Shaw

Randy Shaw is an activist, an attorney, and an author living in Berkeley, California. Born in 1956, Shaw grew up in Los Angeles, California. Shaw attended University of California, Berkeley, graduating in 1977, and then went to Hastings Law School to become a lawyer. Many of his other works focus on other political movements such as immigrant rights or the transgender movement.

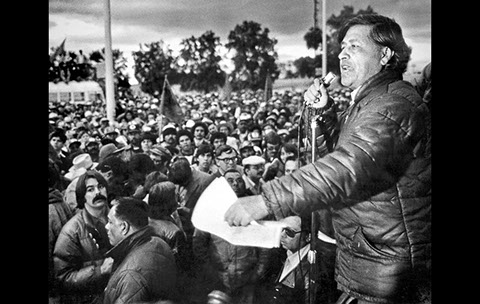

The period of the 1970s was a time of great change that include movements toward a better and more unified America. In Randy Shaw’s book, Beyond the Fields: Cesar Chavez, The UFW, and the Struggle for Justice in the 21st Century, he tells the story of how Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers of America (UFW) “influenced America’s movements for social and economic justice.”1 During this time, Latinos faced racism, persecution, and brutal abuse by the government that encouraged them to migrate to America and yet did not provide protection. Treated worse than animals, Latino workers suffered horrible work conditions, unclean living conditions, poor diet, and faced poverty. Cesar Chavez experienced this inhumane treatment of the farm workers first hand and decided that enough was enough. He was certain that he had to create awareness for the inexcusable injustices committed by the owners of the field and expose the injustice of the government for allowing it. Although he knew that he had the support of many, he also knew there were many more who were reluctant to come forward for fear of losing what little they had. Chavez also knew how important it was to pick the right strategy in order to ensure success and create change.

Shaw’s work focuses much on the UFW’s boycott model, the strategies used to create momentum and get people involved in the UFW, and the legacy left behind by Chavez that continues to influence and empower many to solve the inequality problems that plague mankind still. Strategies used by the UFW in the 1960s and 1970s are often adopted and readjusted or often used to influence many movements today both in labor disputes and in government activities. Although the “alignment between affluent growers and the local Catholic Church posed a challenge for Chavez,” he was able to form an alliance with the Catholic Church allowing the UFW to reach a broader audience and to form a strong relationship between the labor and religious communities that had not been in existence for more than 20 years.2 In doing so, Chavez promoted encouragement for La Causa (the cause) among the religious community by joining protest activities with religious ideas and symbols.

The UFW was also able to encourage many young adults, students, and graduates to participate in the movement to transform the Latino community.3 They helped organize the drive to battle the use of pesticides in the fields due to it causing health problems to the farm workers. Many of those involved who were attending school went as far as stopping their education midway in order to fully support the work of the union – eventually returning to their schooling ten to 20 years later. The UFW was able to provide schooling and development courses that taught their members strategies and skills on how to educate others and get others to join in the fight against the farm growers. These skills that were taught helped many of the young adults to develop useful communication abilities, which continued in their jobs and in their family life.

Shaw also describes the effort of organizing political movements and other electoral activities. The UFW found a way to fight off political attacks from growers by creating an outreach program to include “low-income and Latino voters.”4 Encouraging as many Latinos to vote would help the UFW to have a voice in electing leaders and voting on propositions. They relied on people power rather than bribing and offering campaign donations to ensure change for the future of the Latino population. In order to reach as many people as possible, the UFW organized grass roots election campaigns, which played a large role in changing the results of elections.

Chavez and the union took up the fight for the rights of undocumented immigrants who had little hope for the future. Strongly opposing the way immigrants were treated, there was a public surge for a national immigration movement involving many Latino voters. However, after reaching the pinnacle of success, the UFW began to steadily decline and fade into the past. The weakening was due to the loss of many of the union’s alumni and talented activists.5 Although the UFW faced failure, the model it shaped will still contribute to the way in which unions are formed today and the strategies used to ensure union growth.

Detailing the strategies, goals, and accomplishments of the profound UFW movement, Shaw illuminates the transformation of politics and improvements of social conditions that have come from the work of the union. He preaches that the struggle for justice has gone on too long and needed someone like Chavez to make changes to the way in which people were being treated. Enriched by the groundbreaking practice of the UFW, Shaw writes to tell the story of what it was like to face such challenges and how Chavez was able to overcome them. Chavez’ experience in farm working convinced him to come up with new ways to defeat the power of the growers.6 Although nearly half a century later, the Chavez’ legacy continues to live on and remain a strong force that empowers many to find their voice and use it to create change.

Born in 1956, Shaw grew up in Los Angeles, California, and was exposed to many of the social problems of his time. He began attending University of California, Berkeley in 1977 and while he was there, attended a tenants’ rights campaign and quickly became an activist.7 His activist background predisposed his point of view and makes him partial to the material he writes about. His life has been centered on advocating for rights of those that have had none or were having their rights abused. During Chavez’ and the UFW rise, Shaw was alive and was able to see the causes and effects of the brutality of the growers on the farm workers. However, his swayed point of view also made him more qualified to write on such a topic as Cesar Chavez and the Latino labor movement. His experience with protest and activist activities allows him to show a truthful depiction of the rise and fall of the UFW and how Chavez legacy continues to inspire many.

During the time Shaw began publishing his book, the 2008 presidential election was in full swing and Barack Obama was elected as President. The foundation of Barack Obama’s election campaign models the UFW movement and the strategies used by the members during the 70s. In order to gain as many voters as possible, Obama adopted the “Yes We Can!” rallying cry.8 This emphasizes how the UFW’s message has stretched past the Latino movement to become a well-known, universal message for social and political justice. Similar to the leaders and organizers of Chavez’ campaign, the organizers in Obama’s campaign dedicated large amounts of their time to activism and were motivated to change the way the government would run. Here, we see an example of information combined from the past utilized and ingeniously coalesced with new technology of the present. Shaw was also influenced to write this book because as an activist, he tried to create his own program in 2001 called JusticeCorps. However, the program failed due to a lack of employment opportunities. This made him wonder how successful programs have stayed alive and what they did in order to maintain success. He interprets the success of the UFW is due to its brilliant strategies and tactics that have helped it to thrive and to continue to motivate others.

The reviews by Susan Marie Green and Laura Clawson summarize and analyze in depth the central topics of the book. Although critical, they seem to like the books structure and the author’s purpose for writing the book. They emphasize that the UFW is one of the most important unions that should have more recognition by our society today for its work and its accomplishments in the community. However, Clawson believes that the movement was successful due to a coalition of the various members that developed skills in the UFW and helped organize the movement rather than the success falling upon Chavez alone. They argue that the union’s legacy relies on its ability to transform beyond one audience and to reach many more such as the religious community or the group of young adults looking to have a voice. The difference between the reviews lies within the context of the writing – Green analyzes much of the information in the book while Clawson extends beyond the text and relates the information to other political movements. Using the labor and progressive movements as models, the UFW applies the old techniques such as boycotts and small protests with new ones to get more involved in its action. The book, simple yet complex, demonstrates the non-traditional methods of the UFW to gain momentum and lends contributions to the success of many of the other unions. Chavez’ own public character helped improve the unions appeal and attraction. He emphasized and was strict about non-violence and civil disobedience.9 His moral witness, although highly criticized for not getting the job done, was what helped the movement grow to awareness on a national level. Due to his background in activism, Shaw is able to extend beyond what basic knowledge some may have and goes further in depth into the tactics used by Chavez and the UFW such as the labor clergy alliance.

This book as a whole was extremely knowledgeable and insightful. Similar to others, not much information was known about Chavez or his accomplishments that contributed to the world we live in today. Shaw told the story in a way that differed from other authors – he mentions the importance of Chavez’ role but he makes it clear that the movement would not have continued around a single person and needed the help of the dedicated leaders and organizers. He covers strategies such as conducting consumer boycotts, creating religious alliances, and generating media attention.10 However, when giving the account of a specific time or event, the writing loses appeal and coherence, and often jumps from the past to more recent events. Such a confusing timeline occasionally makes the story hard to follow and creates a disconnection between the reader and the writing. Nevertheless, Shaw’s writing was able to go beyond basic knowledge and give detail about the movement and its strategies. Shaw tells of a story that many do not know and yet they should. He creates awareness of how important the movement was and how it changed many lives then and continues to change many lives today. Shaw’s clear writing, in depth research, and personal experience with activism is demonstrated in his work. Although the book expands broader than the time period of the 70s, Shaw covers the rise and the fall of the UFW, and how it shaped American history. Shaw exposes how the UFW was able to get more Latino voters involved in elections by going door to door and encouraging low-income people to vote. He also highlights how the UFW set the basis for the increase of Latino politicians in Southern California to authority as well as for the immigrant rights movement in recent years. Shaw gives appreciation to the hero that changed the way social injustices should be viewed and taken care of. Overall, Beyond the Fields is a reliable source for anyone searching for information on the activism and strategies of the Latino Labor Movement.

Shaw takes the position of the 60s and 70s being a brutal time for farm workers across the United States. Cesar Chavez had to do back breaking work for the wage of three dollars a day from 6 a.m. to 2 p.m. Shaw’s position on the 1970s was that it was needed for change to be made. He encouraged looking beyond numbers and statistics of progress and focus on how the program could keep growing. During this time, there were many social injustices occurring socially, economically, and politically. After recruiting members, Chavez needed to train them and develop their skills to work out in the field. By a large degree, Shaw portrays the 70s as a continuation of the 60s. Due to the movement beginning in the 60s, there is great continuity between the two eras. However, there is some difference because the 70s mark the time when the movement reaches its peak, setting records with the amount of voters it helped have a voice.11 As a former activist, Shaw recognizes the needs of the people and displays how Chavez was able to help them attain the rights that this country promises. The author feels the boycotts grew as a necessity as the power of the growers were enormous. Chavez believed, as the author did, that the only solution to the problems of farm workers would be in legislation. Chavez supported the passage of California’s Agricultural Labor Relations Act, which promised to end the cycle of misery and exploitation and ensure justice for the workers. When Cesar Chavez started the National Farm Workers Association in 1962 to take up the fight of farm workers severe treatment. Shaw pointed out that without the strategies - consumer boycotts, building an alliance with clergy, connecting environmental and social justice, grassroots “get out the vote” campaigns and putting Latino workers at the forefront of the labor movement – the United Farm Workers union would not have had movement 50 years ago.

During the 1970s, the Latino Labor Movement was on the rise with Cesar Chavez as its leader and the creation of the UFW. Although he is an “icon of a bygone era,” he and the UFW are credited for “inspiring generations of Latinos” and creating a model for peace and social justice that transcends time.12

Footnotes:

1. Shaw, Randy. Beyond the Fields: Cesar Chavez, The UFW, and the Struggle for Justice in the 21st Century. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2008. 4.

2. Shaw, Randy. 78

3. Shaw, Randy. 101-104

4. Shaw, Randy. 9

5. Shaw, Randy. 249

6. Shaw, Randy. 13

7. “Randy Shaw.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 31 May 2015.

8. Shaw, Randy. 8

9. Shaw, Randy. 85

10. Shaw, Randy. 124

11. Shaw, Randy. 201

12. Shaw, Randy. 6

4 - 4

<

>