The Meister of the World

By Nelson Ho

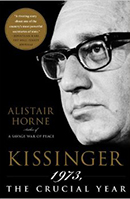

Alistair Horne

Originally from Britain, Alistair Horne moved to the United States during World War II. He eventually graduated from Jesus College, Cambridge as a Master of Arts. After graduation, he took on a job with The Daily Telegraph. As an author, Horne has written primarily on French history, making his work Kissinger: 1973, the Crucial Year, an interesting twist.

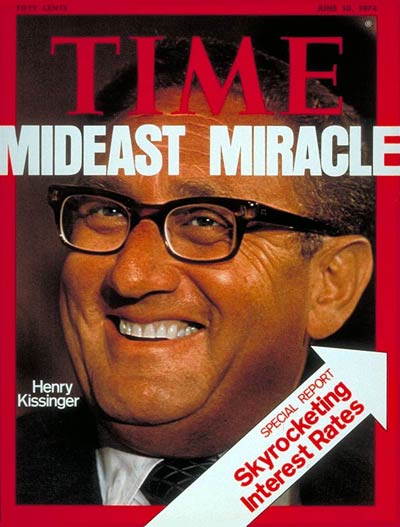

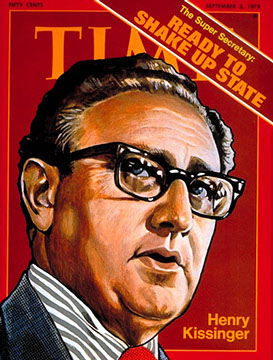

As a tremendous part of Nixon’s presidency, Henry Kissinger represented the backbone of Nixon’s successes and failures. In Alistair Horne’s work Kissinger: 1973, the Crucial Year, Horne comprehensively details the position Kissinger held in terms of foreign affairs. Described as a man that “could tell the same story ten different ways to ten different people and never fib,” Kissinger proved a master of his work.1 His diplomatic skills allowed him to work across the globe, including Vietnam, China, and the Middle East. In his portrayal of Kissinger, Horne often praises his approach. His bias becomes a consistent theme throughout his work due to his kinship with Kissinger. However, as a whole, Horne’s work provides a detailed journey of Kissinger’s life with some added commentary.

Horne begins the work by describing the choice of 1973. It was the year of the US defeat in Vietnam, Watergate, and a collapsing economy, all of which “occur[ed] on Henry Kissinger’s watch.”2 Following his explanation of choosing 1973, Horne transitions into a brief on Kissinger’s background. Born in Germany, Kissinger, a Jew, faced persecution from the Nazis. While in refuge, he met Kraemer who led him to his political ideals. With Kraemer, Kissinger “grew a relationship that changed [his] life.”3 Kraemer sparked Kissinger’s interest in politics as well as instilling the ideals of realpolitik within him. Later, following the advice of Kraemer, Kissinger attended Harvard where he drew upon the ideals of German philosophers Metternich, Castlereagh, and Bismarck. Eventually, Kissinger would meet and become close associates with Nelson Rockefeller. However, in the election of 1968 when Nixon defeated Rockefeller, Kissinger was asked to join Nixon. As a liberal, Kissinger’s pairing with Nixon proved to be an odd one. The two shared multiple contrasting ideals. While Nixon remained indifferent to the media, Kissinger attempted to appeal the media. Yet despite their significant differences, Nixon trusted Kissinger. “If he trusted you, you were in forever; and Henry was one of those.”4 Kissinger had the work ethic of a horse, never letting off the pedal. It was this work ethic that Nixon so admired. But even in his admiration, Nixon held a supreme jealousy for Kissinger and his success. Ultimately, Horne starts off his work with an overview of the year 1973 and Kissinger’s relationship with Nixon.

After introducing Nixon and Kissinger as the oddest couple in political history, Horne proceeds to detail Kissinger’s role in Vietnam, China, Watergate, Europe, and the Middle East. For Kissinger, Vietnam was “the black hole of American historical memory.”5 After Dien Bien Phu fell on May 7, 1954, Kissinger realized the war had obstacles. Moreover, the Tet Offensive of 1968 took the U.S. by surprise, essentially guaranteeing U.S. defeat. In an attempt to end the war through negotiation, Kissinger met with Le Duc Tho of North Vietnam multiple times in secret meetings. The practice of secret diplomacy became a cause of concern for critics. In response to Kissinger’s critics, Horne claims that Kissinger’s stamina allowed the U.S. to end the war without conceding too much. After discussing Kissinger’s affairs in Vietnam, Horne moves onto Kissinger’s affairs in China. Kissinger “saw the opening to China in terms of ‘global equilibrium’ - world balance of power.”6 To open talks with China, Kissinger used the friendship developed between the American and Chinese ping pong teams (Ping-pong diplomacy) as well as secret diplomacy to carry out talks. The talks resulted in Kissinger’s understanding of Taiwan’s importance to China. Most importantly however, Kissinger paved the path for Nixon’s journey to China. However, the success “became the last normal diplomatic enterprise before Watergate engulfed [them].”7 After the Pentagon Papers were leaked by Daniel Ellsberg on June 13,1971, Watergate started to emerge. For Kissinger however, Watergate remained insignificant to him since domestic and foreign affairs were separated. Yet, Kissinger remained grateful that he was never drawn into the affair by Nixon after witnessing Nixon fire two top officials, Bob Haldeman and John Ehrlichman. Horne then follows by providing the critics concern on Kissinger’s relationship to Nixon in the fray of Watergate. Yet, common to his work, Horne shifts the blame off Kissinger and onto Nixon. After describing Watergate, Horne moves to Kissinger’s role in Europe. For Kissinger, Europe “had represented almost the totality of his academic input.”8 Specifically, Europe represented the German background of Kissinger that he proudly represented. In Europe existed the three major players, Pompidou of France, Heath of Britain, and Brandt of Germany. Having met with all three, Kissinger realized the problems in Europe regarding NATO. However, with Watergate occurring in the U.S., focus in Europe floundered and ultimately failed, causing Europe “to be Kissinger’s least successful intiative.”9 Horne continues Kissinger’s failures by discussing his role in the Middle East. Israel’s victory in the Six Day War led to a need of U.S. involvement in the Middle East. With its victory, Israel became a major military power in the Middle East, causing the U.S. to become its new arms supplier. Furthermore, the Middle East remained a large importance due to the Soviet presence. However, Kissinger felt that the Soviet presence in Israel wasn’t large enough to lend help. Almost immediately, critics claimed Kissinger missed an opportunity against the Soviets. Horne then thematically shifts the blame to Watergate. Ultimately, through his description of Kissinger in the major events of 1973, Horne portrays Kissinger as the backbone to both the successes in Vietnam and China and the failures in Europe and the Middle East.

In transition from the Soviet issue in the Middle East, Horne shifts to Kissinger’s role in Russia and the home front. With the Soviets gaining power, Kissinger aimed for peace through Détente and reduction in Soviet rockets. In return, Brezhnev of the Soviets wanted the U.S. to abolish non-aggression treaties and anti-ballistic missile programs. To discuss these issues, the Soviets sent Dobrynin, whom Kissinger came to respect for his sophistication and knowledge. Eventually, through the summit of 1972, Kissinger convinced the Soviets to implement the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT), leading to disarmament. After discussing Kissinger’s success in Russia, Horne continues by discussing Kissinger’s success on the home front. Regarding Watergate, Horne describes how Deep Throat, an informant for The Washington Post destroyed Nixon. Realizing his compromised position, Nixon hoped to be saved through Kissinger by announcing him as the new Secretary of State. Unfortunately, Kissinger had his own troubles with foreign affairs due to Watergate. Consequently, other countries such as Britain began to question the U.S.’s position in foreign affairs. Kissinger even went as far as to state, “the single most corrosive factor was Watergate. The Year of Europe might well have succeeded but for the way the scandal seeped into every nook and cranny of the project.”10 Moving away from Watergate, Horne then focuses on Kissinger and his years as Secretary of State. Horne writes that Kissinger would have retired, “but after the Watergate revelation, I was the glue that held it together in 1973- and I’m not being boastful.”11 Yet Kissinger’s promotion to Secretary of State seemed delayed to the general public. Simply put, it was Nixon’s jealousy of Kissinger that delayed the promotion until the brink of Nixon’s fall. As Secretary of State, Kissinger dealt with events outside of foreign affairs, providing him a break. Also Kissinger received the Nobel Peace Prize for ending the war in Vietnam, a prize that Kissinger accepted proudly. Jealous of Kissinger’s prize, Nixon felt he deserved credit. But indifferent to Nixon’s feelings, Kissinger claims “the major decisions that had ended the Vietnam war had been his.”12 Overall, Horne follows the major foreign affairs with a brief on Kissinger’s role in Russia followed by a enlarged understanding of Kissinger’s success domestically.

After his focus on Kissinger’s role in domestic affairs, Horne shifts back to foreign affairs, the main focus of his work. For small countries like Chile, communism posed a big problem. Salvador Allende, a Marxist, took over Chile following the 1970 presidential election. He would ultimately drive Chile into the ground. However, through Kissinger’s ideas, the U.S. helped organize a coup to overthrow Allende. Eventually Allende would be killed and Chile would be led by Pinochet, leader of the coup. Kissinger’s success in Chile would prove his aptitude for foreign policy. Following his description of Chile, Horne moves back to the Middle East. In a revelation, Israel, Egypt, and Syria enter the Yom Kippur War. Immediately, Kissinger called Dobrynin, the respected Soviet, to determine any possible Soviet involvement. However, his calls proved ineffective as Dobrynin seemingly lied. Eventually, under Kissinger and Nixon’s mastery, the U.S. helped Israel through massive airlifts that allowed Israel to be saved and victorious. Its victory represented “an impact both on detente and the West’s oil supplies.”13 However, problems still loomed due to the disengagement process. Horne describes Kissinger’s trip to Moscow as a “face-saver” for the Soviets and consolidation time for Israel. Furthermore, Sadat of Egypt originally proposed the U.S. to use force to end the war. However, Kissinger knew that was impossible. Eventually, Kissinger and the U.S. declared the situation in the Middle East “DEFCON 3 the highest order of alert in peacetime.”14 The crisis meant to Kissinger the highest degree of alertness that would avoid Soviet suspicion. Too many, DEFCON 3 was the highest point of criticism on Kissinger’s work. Yet, Peter Rodman claimed “it shook the Russians into agreeing on a cease-fire.” 15 Following the Middle East, Kissinger was forced to return to China. Kissinger and Zhou “were not cemented by formal agreements but by a common assessment on the international situation.”16 Essentially, the meeting with the Chinese had marked a high period since they had pushed the Soviets out of the Middle East. For the Chinese, who condemned the arrogance of the superpowers, the Soviets loss was desirable. However, even in the success of the meeting in China, the oil crisis began to loom. In a resistance against the western powers, the Middle East developed the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to resist price reductions. In doing so, they enacted an embargo that caused distress in the U.S. where oil production was declining. In response, Kissinger agreed to withdraw troops in exchange for lifting the embargo, displaying his mastery of policies. Finally, Horne ends his work by summarizing his main ideas as well as explaining Kissinger’s aftermath in returning to Georgetown. Overall, Kissinger’s return to foreign policies as Secretary of State proved successful.

In his work, Horne details the life of Kissinger to display his mastery in foreign affairs. Horne specifically chose 1973 because it was “the year of the signing of the pact to end the Vietnam War, the year of Détente with the Soviet Union, but also the year when all hopes were undermined by Watergate.”17 Essentially, Horne chooses the year specifically because it has both positives and negatives. It allows Horne to portray Kissinger as the foundation to the many successes and failures of the Nixon presidency. Furthermore, he does this by establishing the superior influence of Kissinger in comparison to Nixon. Throughout his work, Horne portrays both Kissinger and Nixon, while always depicting Nixon as the jealous one. By portraying Nixon negatively, Kissinger retains the lime light of Horne’s work. Even in the Nobel Peace Prize accepted by both Kissinger and Nixon, Horne portrays Nixon as jealous. Overall, Horne attempts to portray Kissinger as the central piece of the successes and failures of the Nixon administration.

In thinking of who would write a work on Henry Kissinger, the last man would be Alistair Horne. From Britain, Horne’s works also include The French Revolution, Age of Napoleon, and other works regarding France. Furthermore, he even provides the question, “How does a British writer, fundamentally committed to works on the history of France, suddenly find himself writing about a German-Jewish-American professor, who became for a time- in 1973- the single most powerful man in the world?”18 By posing the question himself, it portrays Horne’s acknowledgement that he himself is inexperienced in the field. As an infant in this field, Horne most likely wrote the novel carefully and with caution. He would be afraid to directly criticize Kissinger as he already deems him the “single most powerful man in the world.”18 Furthermore, he notes his friendship and direct contact with Kissinger throughout his process of writing the work. The direct relationship proves to be a cause for concern of the bias Horne holds for Kissinger. Overall, Horne’s inexperience in the field and relationship with Kissinger leads to a conservatively written book with bias toward Kissinger.

By publishing his work in 2009, Horne produced a work differentiating from the views of its time period. More information had been revealed, specifically regarding Watergate. Moreover, general attitudes on certain aspects of the 1970s have been developed and cemented into society. While discussing Watergate, Horne writes, “Washington Post’s Deep Throat was persecuting Nixon for his ‘immorality’ over Watergate.”19 It was in 2005 that Deep Throat revealed their identity as well as more information on Watergate. Furthermore, throughout his work, Horne references Kissinger’s works multiple times, taking directly from Kissinger’s own opinions written later in his life. These changes since the 1970s helped endorse a new work on Kissinger to provide new details and aspects on the events of 1973 specifically. Overall, the new events up to 2009 most likely caused Horne to write his work to exploit new details later revealed.

In reviewing Horne’s work, The Telegraph and The New York Times both summarize the key points of the novel but hold widely different opinions on Horne’s work. The Telegraph writes, “The author’s expertise is evident in the chapter entitled ‘A Dagger Pointing at the Heart of Antarctica.’”20 The reviewer David Owen seems to enjoy the fact that the chapter takes on a view that criticizes Kissinger. Furthermore, Owen also praises Horne for referring to himself throughout the novel. Finally, he praises Horne on his detail in the Middle East affairs as thinking that there was little left to write about them. Contrarily, The New York Times seems to denounce Horne’s work and style. Reviewer Heilbrunn writes, “Horne also goes badly astray in denouncing the Senate Church Committee hearings.”21 Furthermore, Heilbrunn continues to criticize Horne for his ideas on Chile. However, Heilbrunn does agree that the Middle Eastern affair was beautifully written by Horne. Overall, Horne’s work seems to be a work that falls short of greatness.

For one that hasn’t read much on Kissinger, Horne’s work presents a detailed analysis on the life of Kissinger. Simply put, it provides the entire spectrum. Furthermore, its first chapter is brilliantly written in that it establishes the author’s voice while also creating common themes to the work. However, the work has its downsides. It presents information in a sense favored toward Kissinger. Horne himself even writes, “Certainly I admit to entering the ring with a predisposed respect for the magnitude of what Kissinger had attempted to achieve.”22 However, in general, the book provides a detailed life of Kissinger that only has a downside of bias.

In his work, Horne definitely takes the 1970s to be a time of crisis. He even explains that there were three major crises: “Defeat in Vietnam... Watergate... a collapsing economy.”23 Even in times of Kissinger’s success, Horne always seems to contrast that with an event that proves to fall flat, such as Europe. However, the work doesn’t portray the 70s as a continuation of the 60s. In fact, Horne focuses solely on the 1973, while occasionally taking to 1970-1972.

“Then, as suddenly as I had been catapulted to public service, it was over.”24 Henry Kissinger’s own words depict that even in his mastery of foreign policy, Watergate ended all. Overall, Horne portrays Kissinger as the nucleus to the successes and failures of 1973.

Footnotes:

- Horne, Alistair. Kissinger: 1973, the Crucial Year. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2009. xiii.

- Horne, Alistair. 8.

- Horne, Alistair. 12.

- Horne, Alistair. 25.

- Horne, Alistair. 35.

- Horne, Alistair. 66.

- Horne, Alistair. 88.

- Horne, Alistair. 107.

- Horne, Alistair. 121.

- Horne, Alistair. 176.

- Horne, Alistair. 187.

- Horne, Alistair. 195.

- Horne, Alistair. 264.

- Horne, Alistair. 300.

- Horne, Alistair. 312.

- Horne, Alistair. 338.

- Horne, Alistair. xi.

- Horne, Alistair. x.

- Horne, Alistair. 173.

- Owen, David. “Kissinger- 1973, the Crucial Year: Review.” The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group, 4 Sept. 2009. Web. 25 May 2015.

- Heilbrunn, Jacob. “Got Your Back.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 18 July 2009. Web. 25 May 2015.

- Horne, Alistair. xiii.

- Horne, Alistair. 8.

- Horne, Alistair. 394.

4 - 4

<

>