An Economy Without Power

By Andrew Ton

Franklin Tugwell

Franklin Tugwell received a PhD in political science from Columbia University. He was a professor at Pomona College and an adjunct distinguished professor at the Heinz School of Carnegie Mellon University. He serves as a member of the Advisory Board and International

Committee of the American Council on Renewable Energy.

The effects of the energy crises in the 1970s were apparently sudden and extreme, and “it is tempting…to search for a single critical moment, a point at which decisionmakers turned away from policies that relied on market forces and turned to ones that would…draw the government more deeply into the regulatory quagmire. But there was no such single moment.”1 Franklin Tugwell synthesizes the fields of economics and politics in his book The Energy Crisis and the American Political Economy to look back on the energy crises of the 1970s and how they came to be. Tugwell uses a broader scope to analyze the situation, also adding his own commentary and criticism of the failures of the American government, both past and present.

Tugwell begins his book by providing a solid foundation upon which the reader can begin to develop a complete understanding of the history behind trends in energy. Chapters one through five of The Energy Crisis and the American Political Economy serve to discuss the response of “energy regimes” to the problems they have encountered. “Energy regimes” are, as Tugwell puts it, “the amalgam of private and public arrangements that historically has determined” both the management of specific energy resources and the distribution of its wealth.2 There are four energy regimes involved in the Energy Crises – coal, oil, natural gas and electricity. Coal saw stability and relative prosperity two decades prior to the crisis, as it was “America’s secure, domestic fossil-fuel alternative.”3 However, with a lack of federal intervention, coal fell prey to domestic problems and issues with market management. Oil was too dependent on foreign sources, as foreign imports were cheap, while domestic oil had to balance production; if the production was too high, the industry would collapse as prices would be too low to sustain the cost of production. Natural gas was cleaner and more manageable. It was plagued by a consumer versus producer conflict that resulted in “a kind of degenerative instability.”4 Electricity was relatively tranquil as a legal monopoly. It avoided problems and grew quickly, but was the most shocked by the crisis, as demand dropped and construction costs drastically rose with inflation.

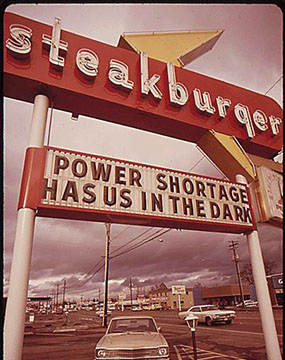

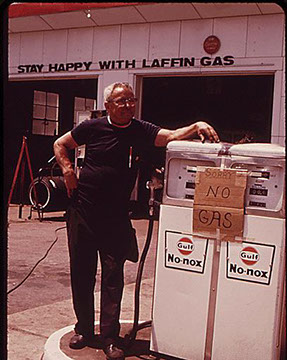

Tugwell aptly titles the next section “Crisis and Response” – after introducing the reader to the background of energy, he now looks at the specific events of the crises. In Chapter 6, Tugwell gives the origins of the crisis, analyzes the different responses by Nixon and Congress, and discusses regulation and later deregulation under Ford. The Crisis in 1973 occurred because “the oil ministers of the Arab oil-exporting countries decided to impose production cutbacks in order to demonstrate their market power and to draw Western attention to the Arab cause” in the context of the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War.5 But Tugwell does not intend on analyzing the foreign event that is the Yom Kippur War; instead he focuses on how the United States responded to it. Nixon’s response can be summarized as damage control. The best course of action, Nixon concluded, was to pursue complete energy self-sufficiency by 1980. Hoping to lower demand for fuel and increase domestic production, he put additional funds into alternative energy and further development on oil, coal and nuclear power. Congress’s response to the embargo was to further price controls and force allocation – government control of resource distribution. Oil was divided into tiers prior to the crisis – old oil was oil that had been found and was in the process of production, new oil was oil from smaller wells and imported oil. Old oil was strictly controlled, while new oil was uncontrolled.6 After the embargo, companies involved with old oil had a clear advantage, as new oil was significantly more expensive. To solve this issue, the government furthered regulation into “the now infamous ‘entitlements’ system”, where companies involved with new oil were given compensation – this is one of the main topics of the book: compensatory regulation.7 Ford sowed the seeds for decontrol, but failed to get it through Congress during his term. Chapter 7 discusses Carter, Reagan and the ending of the Crisis. Although prices rose drastically, it failed to lower consumption, exacerbating the domestic issue. Under Carter, pro-regulators and deregulators compromised. Carter continued the trend of being unable to pass deregulation through legislature, but won provisions providing taxes and subsidies to promote conservation and forms of renewable energy.8 But when Iran collapsed in revolution in 1798 and stopped exports outright, OPEC leaders quickly took advantage of this and raised the oil prices once again – Tugwell calls this the second oil shock. As the Carter administration ended, consumption fell with the development of more conservative uses of energy and the loosening of the international market. Indeed, the energy crisis ended under Reagan as the market stabilized and deregulation took hold, undoing price and allocation controls.

Tugwell then comprehensively examines both U.S. policies’ accomplishments and lack of accomplishments leading up to, during, and after the crisis. To alleviate the pressures of the crisis, the main solutions were to reduce consumption and to reduce the vulnerability or dependence on foreign imports. In doing so, demand would drop and prices would drop. Unfortunately, public energy policies worked against each other. Some reduced consumption and vulnerability, while others encouraged it; as Tugwell puts it, “government energy policies…worked against each other.”9 But worst of all, Tugwell states that “the net effect of government policies appears to have been to increase the level of import dependence, petroleum consumption, and energy intensity beyond the levels they would have otherwise attained.”10 In saying this, Tugwell clearly criticizes the energy policy at the time. The aforementioned entitlements system encouraged businesses using expensive imported oil to continue doing so, as the government guaranteed that they would be compensated – the entitlements system clearly encouraged an increase in imports, heightening vulnerability. In Chapter 9, Tugwell revisits the energy regimes. He suggests that the lack of unified decision-making across the energy regimes and a lack of prior energy policy, as the U.S. had never had an issue with energy before, made the severity of the Energy Crisis possible. Each of the regimes had their own issues, despite appearances. Coal should have burgeoned from the crisis, as it was a strong domestic industry – yet it was plagued by miner complaints, strikes and environmental concerns. Natural gas was scarce, as it had both low supply and low prices as a result of price regulation, so there was little incentive to expand the industry. Demand was high, however, and it was deregulated in 1985. Electricity was stable and predictable until the crisis, with steady increases in demand and production. Once the energy crisis struck in 1973, demand fell off and production costs skyrocketed with more expensive fuel needed to produce electricity. Utility companies suffered greatly, but survived as a legal monopoly. As Tugwell puts it, “the energy crisis was first and foremost a crisis of wealth distribution.”11 Various interests worked to avoid losses while others tried to address the problem, leading to stasis in legislation. Consumer interests and producer interests conflicted, further paralyzing the nation. Nixon’s push to regulation exacerbated the problem, and it took much effort to pass deregulation, ending the crisis.

After all of the analysis, Tugwell draws his conclusions and pulls lessons from the events and issues of the energy crisis. Tugwell begins by stating his purpose: “Very few serious analysts adopted a broad enough perspective to allow a balanced evaluation of what was done in relation to the political and institutional imperatives of the democratic polity.”12 As such, Tugwell writes to use a broad perspective to best analyze not just politics or economics of the energy crisis, but the political economy and how it was involved in the crisis. Tugwell is not satisfied with the actions of the United States – its failures led to increased energy vulnerability and hurt the consumers. He goes on further to say that there needs to be a new policy, as the old one will eventually fail. He criticizes the resistance to redistribution of wealth as condemnatory to the nation’s prosperity. Tugwell believes that “the lesson learned from the cycle of failure in regulation is that the government is incompetent, the private sector untrustworthy.”13 From this, then, Tugwell begins to pitch the idea of markets by design, or planned markets. In this “most radical model of political economy… the government accepts responsibility for the operation of the economic system and the values it promotes, but wherever possible eschews detailed regulation or micromanagement, instead relying on competitive, or marketlike, processes”, a drastically altered course for the political economy.14 And yet it seems the most promising: it fosters competition that benefits all parties, it requires a very involved government that is active but not oppressive. When applied to energy, it promises unparalleled economic efficiency and mitigation of past problems. However, due to ideological opposition and the necessity of a drastically restructured American political system in order to implement planned markets, Tugwell believes that America’s future is grim.

Throughout The Energy Crisis and the American Political Economy, Tugwell states and reaffirms that the United States’ response to the energy crisis, compensatory regulation, served only to exacerbate energy vulnerability. Tugwell writes that “from 1973 to 1983 the net effect of government policies appears to have been to increase the level of import dependence, petroleum consumption, and energy intensity beyond the levels they would otherwise have attained.”15 To fully use a broad perspective in writing this book, Tugwell makes it clear that he incorporated both economics and politics into the study of a political economy. This political economy, Tugwell suggests, is what ultimately led to the unsatisfactory energy policy during the crisis. As the policies increased import dependence, America became more vulnerable to foreign influence. Likewise, as petroleum was consumed at a higher rate, demand grew for petroleum, a demand that encouraged greater importation.

Franklin Tugwell received a PhD in political science from Columbia University. He was also a professor at Pomona College and an adjunct distinguished professor at the Heinz School of Carnegie Mellon University. He serves as a member of the Advisory Board and International Committee of the American Council on Renewable Energy, among other boards related to international development. He was once the president and CEO of Winrock International, helping to overcome rural development challenges like energy, economy, agriculture and business. Clearly, Tugwell is an expert in his field, and is very qualified to write about energy policy. His bias lies in the high positions he has held – Tugwell is often very critical of the government’s actions, as he sees the situation from an insider’s perspective. His point of view is summarized when he writes “We are in serious jeopardy when it comes to managing our increasingly complex, technologically sophisticated economy. The efforts of our government, though well-intentioned, did precious little to resolve…the issues raised by the crisis.”16 As this book was published in 1988, five years after the crisis is considered over in 1983, it has adequate perspective to analyze the events and policies, seeing the early aftermath. However, as the energy crisis was still very recent, there was a great amount of reactionary public discontent that always follows these kinds of large public issues. All of this is reflected in Tugwell’s conclusion where he deliberates the idea of planned markets, explaining a possible solution to future crises. Tugwell’s purpose for writing this book is directly related to the time in which it was written, 1988: to expand the narrow scope that economists and historians had been using up to that point in analyzing the energy crisis. Tugwell fits the attitudes of the educated, providing analysis of events with a critical point of view of government decisions.

Two critical reviewers, B. Dan Wood in The American Political Science Review and John G. Clark in The Journal of American History give different interpretations of Tugwell’s writing. Wood writes that “the Tugwell book evaluates energy policy from the broad perspective” and “locates current energy policy in the context of historical development, which enables predicting future responses to oil shocks.”17 Wood believes that Tugwell provides a depth of understanding of energy policy, but does little else. Meanwhile, Clark believes that “Tugwell’s analysis of American initiatives to create a bloc in opposition to the OPEC is weak and controverted by some recent studies”, and that “Tugwell’s exposition…hangs large generalizations on a skinny structure of evidence.”18 Clark calls Tugwell a utopianist, as he was calling for massive political reform to institute planned markets. These two reviews poke at the weaknesses inherent in Tugwell’s work. It is very much a useful resource but is limited as an early work, weakened by future studies.

Although these reviews peg Tugwell’s work as such, the book remains a very comprehensive analysis of the events and policies involved in the energy crisis in a unified analysis of the interplay of economics and politics in a term dubbed political economy. It is undeniable that Tugwell’s writing was at times weakly supported. Such is the fate of the earliest treatises on any topic. But these works are necessary as a foundation to support further study, and Tugwell’s writing excelled in this regard. His analyses of government action is invaluable; for example, Tugwell writes that price controls were “chosen temporarily in the first few months of the crisis [but] became locked in, and could only be changed when the distributional issues it addressed had resolved themselves. This deadlock in the polity, more than anything else, explains the character of national energy policies.”19 Tugwell’s work in closely analyzing the issues central to the energy crisis makes his writing very utile for those looking to understand the political and economic disaster that was the energy crisis of the 1970s.

Tugwell very much portrays the 70s as a time of severe crisis in the United States. He recognizes the energy crisis as an issue so large as to be acknowledged as “the most damaging and disruptive economic debacle since the Great Depression.”20 Clearly, Tugwell supports this throughout his book by declaring the failures of both the executive and legislative branches of government in their responses to this crisis, both in domestic and foreign policy. But Tugwell also devotes a large portion of his writing in analyzing how these issues came to be. Indeed, he clearly delineates the energy crisis from the 1970s and 1980s as a result of problems already extant issues in the 1960s. Tugwell writes that “all these trends were in evidence before 1973, but the crisis added impetus to them” when discussing the various energy regimes and how they reacted to the crisis.21 He visits the presence of patterns when he writes that “energy policy was the result of a series of incremental decisions…all heavily influenced by the existing pattern of energy regulation and by political pressures.”22 Tugwell believes that the crisis was already visible before it even happened – the energy crisis in the 1970s does not surprise Tugwell, as he sees it as a clear continuation of the 1960s and even the decades before that, going as far back as to analyze Depression-era policies.

The energy crisis was “a major crisis of redistribution, fomenting conflicts between individuals, organizations, and whole regions of the country over the allocation of losses.”23 As oil prices rose to ten times those before the embargo, the energy industries felt a strain like no other. The crisis sent billions of American dollars overseas and overturned domestic energy policy; it serves as one of many reminders of America’s weakening grasp on the world and its failing foreign policy.

Footnotes:

- Tugwell, Franklin. The Energy Crisis and the American Political Economy. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1988. 111.

- Tugwell, Franklin. 5.

- Tugwell, Franklin. 23.

- Tugwell, Franklin. 77.

- Tugwell, Franklin. 97.

- Tugwell, Franklin. 106.

- Tugwell, Franklin. 107.

- Tugwell, Franklin. 118.

- Tugwell, Franklin. 147.

- Tugwell, Franklin. 147.

- Tugwell, Franklin. 187.

- Tugwell, Franklin. 194.

- Tugwell, Franklin. 211.

- Tugwell, Franklin. 222.

- Tugwell, Franklin. 147.

- Tugwell, Franklin. 3.

- Wood, B. Dan, Franklin Tugwell, and Eric M. Uslaner. “The Energy Crisis and the American Political Economy.” The American Political Science Review 84.2 (1990): 677. Web.

- Clark, John G, Franklin Tugwell. “The Energy Crisis and the American Political Economy.” The Journal of American History 76.4 (1990): 1331. Web.

- Tugwell, Franklin. The Energy Crisis and the American Political Economy. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1988. 187.

- Tugwell, Franklin. 1.

- Tugwell, Franklin. 189.

- Tugwell, Franklin. 111.

- Tugwell, Franklin. 2.

4 - 4

<

>